Last week I had the privilege of visiting sock knitting mills in Hickory, North Carolina. I followed up those visits with a weekend in Manhattan.

The stark contrast between these locations is well worth reflection.

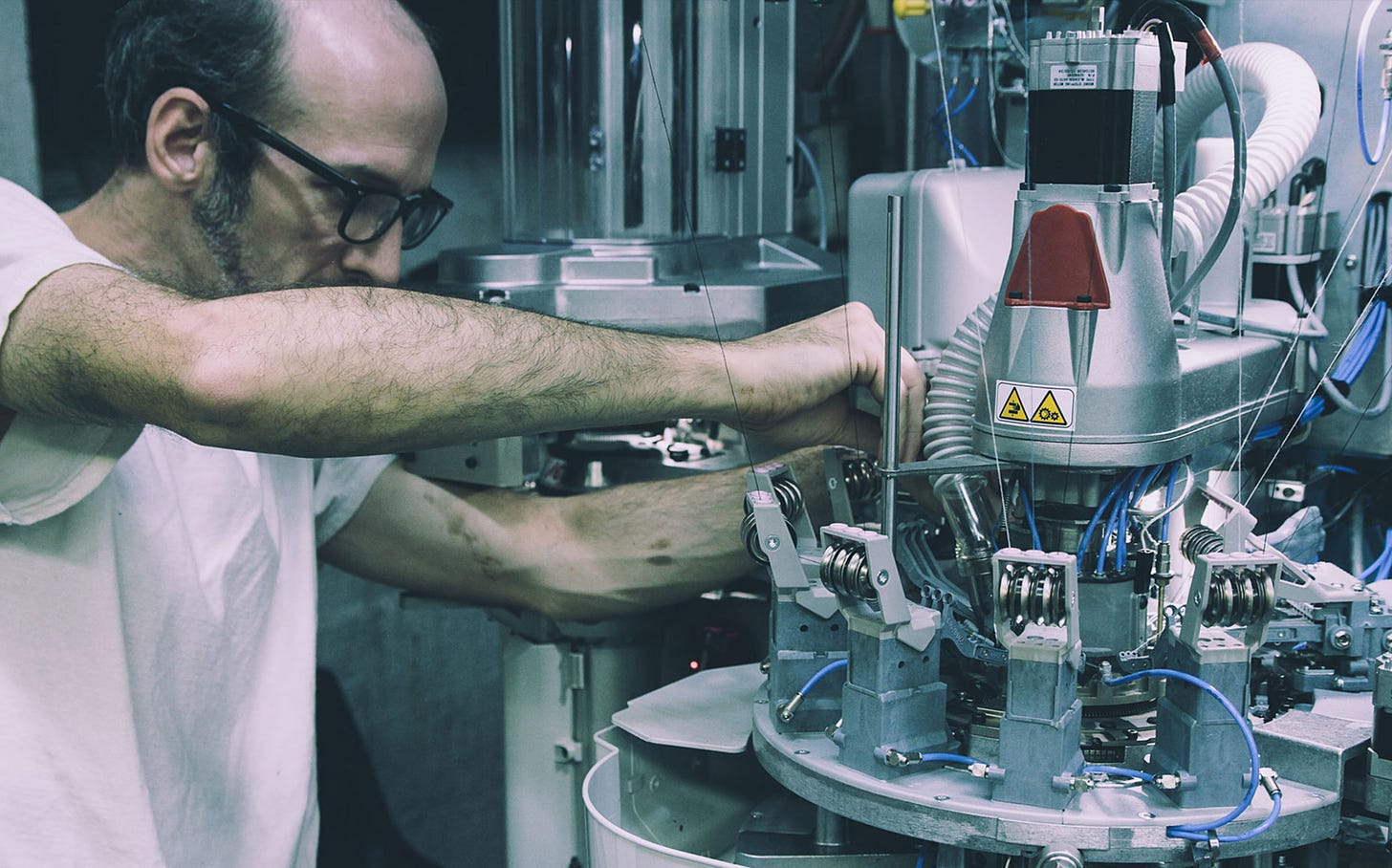

Hands on machines - grease slicked, humming and hot - pumping their thread through like water. Cotton spun yesterday, now knit into cylinders, into toe boxes, into footbeds and into welts.

Note: a Knitting Mill is not a collection of grandmothers knitting thick spools of yarn into socks. Socks are knit on machines: Lonati, Uniplet, Sangiacomo. They sound more like soccer players than means of production. Make no mistake; these are big droids that spit out a whole sock quicker than you’d eat your lunch. But knowing how ten, twenty, a hundred of these machines work all at once? You might find it hard - and you’re right. It’s even harder to do than you’d think.

The sound. The sweat. The work.

A thousand miles away, banking builds, floor by floor, ever taller self-serving reminders that finance and property go hand in hand like golf polos and khakis.

Compare Manhattan’s monoliths to the flat flat, more stuffed than sprawling knitting mills of North Carolina and you’ll ask yourself too why the inhabitants of the latter reap the lesser wage.

But then again, the answer to all of your questions is money.

The same hot and humid, they somehow both were - a moist reminder that these places - North Carolina and New York - can exist in the same country, let alone on the same planet. These places so different that the people in them won’t even think about the others except for what they stream on Netflix or see on the news.

Down there, dead deer on the wall. Paintings and pictures of ducks and bears and lions and Dick Cheney too. Oh my.

A factory and a city street. Almost identical in their volume, their constant motion, and maybe even some shared desperation. People talk about New York in this way, all the time. But people don’t talk about regions like Hickory - places with just as much grit as any - nearly enough.

While one’s neon and the other one’s wood, they both grow into familiar forms of themselves, persistent to the last stitch in being proud of who they are, resistant to changing too much, but still evolving all the time, sweating and bleeding the whole way home.

American factories, before they became popular gentrification projects, were the backbone of our economy.

The working class existed beside big hot machines on wood floors under low roofs. Central air, if they were lucky, but probably not. Manufacturing dominated flights of American society in New York, in Pittsburgh, in Cleveland, in Philadelphia. Now these cities do not so much lament their evolution into tech and healthcare and banking as they do seemingly boast their blue collar pasts on their expansive (and expensive) paths towards “urban renewal.” You can’t blame them. Riverfront property will always be worth its weight and then some.

Being from those places and not so much witnessing, but hearing about the exodus from the mill to the Macbook, it’s easy to gradually forget the important beginning to the jobs and the people that in large part built our country. Unless you watch hours of how it’s made or Modern Marvels, you’ll forget the story of American manufacturing.

But that story is still being spun in Hickory, North Carolina.

For the folks still working in the factories there, made in the U.S.A. is more than a hashtag. To call it a way of life would even insinuate that there was some kind of choice being made for the sake of morality, patriotism, or spiritual fulfillment. The work being done in Hickory is entirely necessary for all parties involved - and while business is good, their trades are becoming harder and harder to find all the time now.

These people become reminders of what we once were, what we still are and what we can be. They’re a testament to the value of hard work. Private, proud, but entirely aware of the endangerment of their species, the factories we visited have names unfamiliar and unimportant to anyone outside of our industry. But across the board - from spinning to knitting to packing to shipping - it’s remarkable that that the products made there only cost what they cost. The Retro Stripe (the OG American Trench product) alone touches ten or eleven hands before we snap it on a foot model. And while the machines surely matter (at thirty thousand a pop, they better), the mill workers mean more. Someone has to load the yarn onto the fingers. Someone has to keep the machine clean. Someone has to sew the toes shut, fold, package and ship the things out into the world.

In a way I think the workers in these factories find what I do to be suspect - taking pictures, asking too many questions, finding what they think is day-to-day as a fascinating blast from the past. But these places aren’t so much relics of a manufacturing world no-longer as they are reminders of how important human touch can be in a world full of machines.

“Saving time is saving money. But automation cannot equal elimination,” a factory owner said to me. “Finding places to put skilled workers into our processes to ensure quality is the best way to make a quality product and our people employed.”

I don’t think that notion solely exists in a knitting mill.