Avoiding all spoilers here. This film’s been on my mind for a week. Big showing at the Golden Globes last night as well. Slight review on why I think it’s great – I’m sure I’ll look back on this after a re-watch in a few years and cringe but while it’s fresh….

There are hundreds of movies about great men.

The biopic, for better or worse, has become so engrained in our society that we now seek it out in other mediums, too – TV shows, podcasts, Broadway musicals.

It gets a little stale, doesn’t it, all those movies about boys who got bullied, who were too short to earn daddy’s approval, whose brother had their arm removed in a mill accident, to then prove everyone wrong, and write lots of country songs, invade Russia in the winter, or build a big bomb.

Biopics are all about casting and editing. It is impossible to boil someone’s essence into 180 minutes. It is impossible to not judge Austin Butler’s performance as Elvis and not compare him to Elvis. And it is impossible to play Michael Jackson and not try and be a kind of Michael Jackson. At a certain point, performing a role as Elvis Presley is entirely about your Elvis Presley impression. If that was great acting than Jim Carey should win an Oscar, every year. Impressions are fun, and can even be funny. But I do not think that they are a sophisticated form of entertainment. Pawning off someone’s own likeness is a mediocre art form.

For me, biopics struggle to develop a true nucleus. A mission statement. A theme. How can I make meaning from a life that’s been lived – and lived so publicly that someone years later made a f*cking movie about it. I am not sure what themes you can pull from someones biopic beyond that of what they themselves sought out in their own lives. Persevere! Dig deep! Keep going! Stay humble! Dance to the beat of your own drum!

How many different ways can we skin the same cats?

Stories and their meanings will always be about theme. Theme – oversimplified here – is the message. At least this was how I taught theme at Webster Middle School. Preposterous to write to the reader now as a 7th grade boy or girl? Perhaps not, depending on how you felt about Rocket Man. Theme is your thesis statement. Your comment. Your critique. What you’re trying to say.

It sounds combative to call all artwork an argument. Better to say: any art without a point of view is likely bad art. The stronger the point of view, the smoother it is to make choices.

And therefor a biopic’s point of view, which is so often a repossession of someone else’s point of view, can be characterized as flat. Two dimensional. There is a point A and a point B. You can fill what’s between them with what you read on Wikipedia.

Biopics are criticized for their bad aim. There won’t be a Big Ben Roethlisberger biopic but if there was, they definitely wouldn’t talk about that bar in Georgia 2005. These films lose their teeth. They become propaganda pieces for their subjects. Everyone knows they can’t root for a villain.

And if we know anything about great men, it’s that they are often times just that: the bad guy all along.

So when we get films like There Will Be Blood or TV shows like Breaking Bad, we are not surprised when the great man at the center of the work is not so great after all. In fact we root for the breaking of bones. Their deceit and their cunning. We squirm with delight during the clandestine affair. We cringe through covered eyes when greed fills the faces of the men we’ve been rooting for all along.

But something about the very flawed, very villainous, very fictional characters feels more real than the dead ones.

Last year, what many considered the best film of the year, Oppenheimer, remains, while not the most recent, but perhaps the most relevant for this conversation. Oppenheimer is certified fresh. But it is an exploration of a real person who achieved feats of physics and the film itself takes on the depiction of those physics as it’s own task to bare. Oppenheimer without inventive particle smash is a history channel movie. If it’s to be Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer… well it damn well should be visually, sonically, physically stimulating. Oppenheimer became a film about the how it was being told. Not so much about the why, or the what.

Enter: The Brutalist. A film concerned with all three. A film with a point of view. (Spoiler: I don’t know what it is yet).

I am an American mutt. I am German and Irish. I am Polish and Welsh. I am Italian although not sure where from but it says so on the website. But the part of my blood of which I feel the most connected is the eastern European particles. For me the wedding sequence (a movie unto itself) from Deer Hunter is a fingernail above the same type from The Godfather. It’s the slavic in me. I screened Deer Hunter for the first time about a year ago and its locality struck me. They’re from Pittsburgh. They drink Iron City. They play pool and watch the Steelers. It felt like a movie about Slavic-Americans. It felt like watching a movie about my family.

I did not know much about The Brutalist before the trip to the Upper West Side on New Year’s Day. I knew Adrien Brody was the main character. I knew he played a Hungarian-American Jewish architect. I knew it took place after World War II. I knew it was three and a half hours long and I know there was an intermission. Those were enough facts for me.

Again, the slavic in me.

In writing this I realized that Hungarians are not slavs. They actually belong to the Uralic language group despite being quite far away geographically from other Uralic nation-states like Finland and Estonia. I also re-discovered that Hungarians are also known as Magyars.

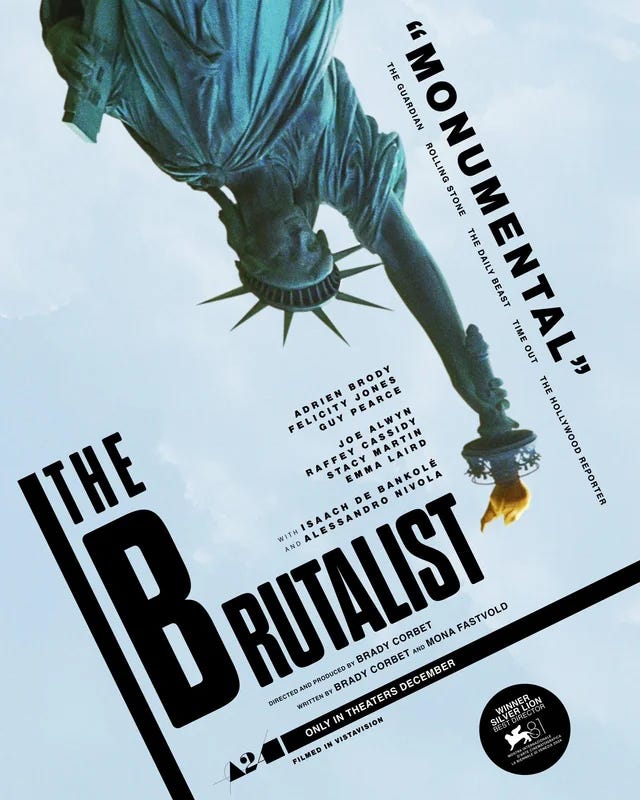

The film has been described as monumental – A24 has hilariously quoted multiple reviews that used the word as a part of the distribution group’s promotional materials.

And it is indeed. Despite its modest budget ($10 Million), The Brutalist does what so many major biopics cannot. It is not concerned with making its man great. It is concerned with telling the story of an immigrant whose dreams do not shatter, nor shimmer. Whose past is not forgotten, nor celebrated. This is not an existentialist film, but it’s central character is a man who is unsure how he got there, if he wants to move forward, if he wants closure, revenge, to be remembered, to be forgotten.

I am not even sure if his work is good. I don’t know anything about architecture. I actually think the library he renovates in act 1 looks… better (?)… before he makes it as minimal as possible. I am still collecting my thoughts to decipher if this is a theme for the film: brutalist art and architecture, which is canonically the architectural response deployed during late 1940’s European reconstruction; which is canonically minimal; which is canonically devoid of detail; which canonically lacks all superfluous detail; which canonically is, among some contemporary architects, especially those who prefer Gothic, or Baroque, or Classical architecture styles, effectively, ugly?

Is Laslo Toth, a Hungarian Holocaust survivor, a once great architect whose art was tossed aside by the third reich, who can now only be commissioned to build bowling alleys, actually making ugly art? And maybe doing so on purpose? To slight his oppressors, past and present?

I don’t think that’s the theme here. But at least I had to think about it. Am still thinking about it. I haven’t thought for a minute what Bohemian Rhapsody, or Jackie, or Lincoln, or Ali, or Ray wanted me to think about beyond what hit me on the nose when I walked in and what slapped me on the ass when I walked out.

I felt a similar way about Laslo Toth that I did about Michael Vronsky. Men who seem to have more guts and a deeper understanding of themselves then the other men around them, but without the words to say it, and with their own imperfections, their own crosses to bare. Laslo and Michael, to me, are honest, real, and on-theme representations of what eastern-European men are like. Sometimes proud. Sometimes humble. Sometimes patient. Sometimes mean. But who they are and the way that they market themselves to other men is not loud. Something distant within them that the other characters and the viewer both cannot touch. They are not larger than life. They are not charicatures. They are not heroes. And they are not great men.

This film has nuance. It’s quietly provocative. It’s a conversation as much as it’s a monologue. As I said before… I’m still wrapping my head around it.

“Is there a better description of a cube than that of its own construction?”

Now that is a point of view.

I will be thinking about that quite a lot in the next few… years.

I encourage everyone to see it and I hope to talk about it with you sometime soon.

Someone’s “essence” indeed. How can that ever be portrayed by another? I wonder as well.